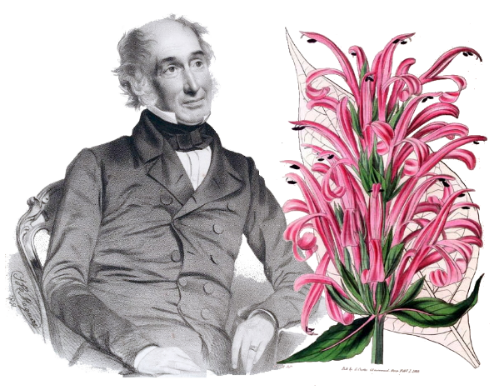

Man With a Plant

On July 6, 1785, botanist Sir William Jackson Hooker was born. Always interested in botany, he collected and organized plant specimens from his earliest years. With his discovery of a new moss, Hooker was elected a Fellow of the Linnaean Society and, at 21, launched his formal career. He was a popular lecturer and appointed Regius Professor of Botany at the University of Glasgow. While there, he assisted Samuel Curtis with his family’s Curtis’s Botanical Magazine. Hooker, like many scientists of his day, was also a skilled draftsman, and contributed impeccable drawings to the Curtis for handcolouring. Hooker valued the talents and friendships of fellow botanists and botanical illustrators, maintaining friendships and both involving and rewarding their efforts throughout his sequential careers.

When Hooker was chosen to take over the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, as its first Director, he determined to make the gardens the centre of botanic science for the country and beyond. He used his life-long contacts to acquire and encourage contributions to a herbarium, a collection of dried botanical specimens, where, as the fine conservator he was, Hooker employed his cat to deter mice from eating the tempting specimens. At his death, Hooker’s personal collection was added to the herbarium that today holds millions of botanic examples and is an irreplaceable collection of original specimens from which new species taxonomy and descriptions may derive.

He organized the outdoor gardens in a scientific manner and expanded their grounds. A master networker, Hooker encouraged the British Admiralty, its expeditions, land explorers of every type, other botanists and herbaria around the world to engage in ongoing, systematic collection and exchange for both the Herbarium as well as the gardens. He had glass greenhouses built, and, most famously, commissioned The Palm House, specifically created for large tropical plants and exotic palms. He established the Economic Botany Collection to illustrate how humans use plants around the world that establishes links between botanic and cultural diversity. To house the ever-expanding samples of trees and wood that continued to arrive from his world of explorers, he commissioned another giant glass structure, the Temperate House.

Hooker made large portions of the Royal Botanic Gardens available to the public throughout the week and published a guidebook for information and enjoyment. Even a city-bound child or adult could taste Kew’s adventure and be an explorer!

Rounding out his long-term vision, Hooker applied his talents to seed a library, welcoming donations of books and papers and solicited a budget for purchasing acquisitions. Today, Kew’s library holds one of the world’s most important botanical reference collections that include letters, plant drawings, and historical photographs.

The Kew gardens have compiled and conserved uninterrupted studies of plant diversity since their creation in 1759. From the outset of Hooker’s directorship, the gardens stuck to its original purpose in collecting specimens and exchanging botanical expertise throughout the world. The cataloguing and careful, specific housing of species that Hooker initiated now supports conservationist efforts in tracking endangered species. The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

B Bondar / Real World Content Advantage